I’m a big fan of Barbara Harris, make no bones about it. She’s a fascinating performer with a unique comic sensibility. For musical theatre fans, she’s most famous for her two back to back shows On a Clear Day You Can See Forever and The Apple Tree, earning Tony nominations for both (and a win for the latter). These are performances that theatregoers of the 1960s are still talking about today. I think in part it’s because Harris never returned to Broadway after The Apple Tree (Walter Kerr deemed her performance in the Bock & Harnick show “the square root of noisy sex”).

Harris found relative stardom in Hollywood in Robert Altman’s Nashville, Alfred Hitchcock’s Family Plot (as a phony medium), and as Jodie Foster’s mom in the first Freaky Friday. She was also Oscar nominated in 1970 for Who is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me?, but shifted out of show business in the 80s and 90s (her last film role was in Grosse Point Blank in 1997). In a 2002 interview she claimed that she was more interested in the acting process than fame or even being successful, and says she doesn’t miss performing (definitely our loss).

Here’s a glimpse at her performance in On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, from a Bell Telephone Hour special on Alan Jay Lerner in 1966. She is joined by co-star John Cullum presenting a series of numbers (“Hurry! It’s Lovely Up Here!,” “Melinda,” “On the S.S. Bernard Cohn,” “What Did I Have That I Don’t Have?” and the title song). The musical itself is truly original – Lerner was interested in exploring ESP and reincarnation. Originally I Picked a Daisy, it was to have a music by Richard Rodgers. However, Burton Lane eventually wrote the music (Lerner and Lane previously worked on the 1951 musical Royal Wedding for MGM).

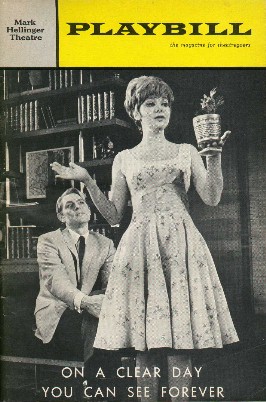

The show played the Mark Hellinger Theatre for 280 performances. There was chaos during the try-out in Boston. Lerner was taking amphetamines at the time, and that got in the way of his writing. Original leading man Louis Jordan was let go in Boston, as were several other actors whose roles were eliminated. The show opened in NY to less than stellar reviews, but Harris’ kooky Daisy, a girl who hears phones before they ring and can talk flowers out of the ground, charmed audiences. The original cast album has preserved the best of the show – namely the cast and the beautiful score. There have been attempts to revise the show almost from the outset, but will be seen in a wholly new version opening on Broadway in the fall (Daisy is now David). And the less said about the 1970 film adaptation, the better.

%CODE1%