To Whom It May Concern,

Four years ago, a beautiful production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific opened at the Vivian Beaumont to acclaim and plaudits all around. One of Lincoln Center’s boasts was the full size orchestra in the pit. The first of many thrilling moments came about one minute into the show’s overture. During a thrilling swell of the “Bali Ha’i” motif, the Beaumont stage retracted to display 30 musicians. I was fortunate enough to be at the opening night of this production, and witnessed for myself the cheers and tears (my own included) from an appreciative house. As the final notes played, the audience roared their overwhelming approval. While the melodies are the creation of Richard Rodgers, the man ultimately responsible for this stirring overture was the brilliant orchestrator Robert Russell Bennett.

It was brought to my attention earlier today by Drama Desk-winning orchestrator and arranger Stephen Oremus via Twitter that the Drama Desk committee has unceremoniously dropped the Best Orchestrations Award from this year’s honors. I can’t help but express my great displeasure at this decision. No official reason was given, and I can understand that, because there is no discernible excuse for this short-sighted and disrespectful snub.

I admire orchestrations. I admire orchestras. I love hearing how a melody is colored by instrumental arrangement, whether it be the romantic sweep of South Pacific or, say, the buoyant percussiveness of Irma La Douce or the big brassy “Broadway” sound of Mame. There is craft and artistry involved here. A composer doesn’t just hand a song to the conductor and the musicians can just magically play it. That might be the sort of thing that passes muster in ancient movie musicals, but the reality is that a song goes through a considerable gestation between the composer’s pen and the orchestra pit (with a nod to vocal and dance arrangers as well; other unsung heroes).

Orchestrators must understand the size, the scope, the intent and the economy involved in building a show from the ground up. Some composers know precisely how they want their show to sound, and may even be gifted in orchestrating themselves, and some may not know a quarter note from a hole in the ground. Orchestrator Hans Spialek likened the task to painting: “with the exception that in musical theatre one man (the composer) furnishes a sketch from which another man (the arranger) paints the musical picture the audience actually hears.” It is rare that a composer does his or her own orchestrations. Arranging a score for an orchestra is hard work, it is time-consuming and a composer generally must be free to revise and write new songs as a show develops.

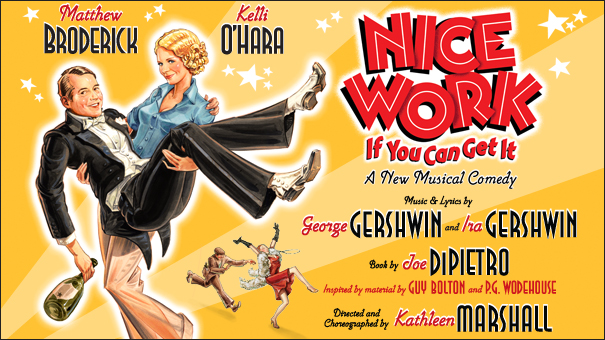

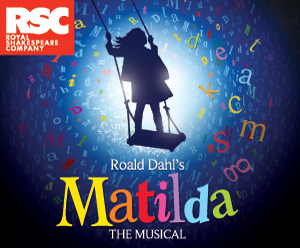

While I have had varied reactions to the musicals of this season, I didn’t have any complaints with the orchestrators. I’ve heard work by the likes of John McDaniel, Larry Hochman, Doug Besterman, Michael Starobin, Martin Lowe, and Bill Elliott, among many others. We have seen show orchestras get smaller and smaller. More and more, it seems that musicians are hidden offstage or in another room (or building) entirely. Many of these orchestrators are forced to make less sound like more, itself a marvel of invention and craft. I can’t help but feel that this snub is just another step in the marginalization of live music in musical theatre.

Orchestrators are artists. They deserve the recognition and respect they have earned through their hard work. I do hope you reconsider this egregious decision.

Sincerely,

Kevin D. Daly

Theatre Aficionado at Large

PS: Every one of you would benefit from reading Steven Suskin’s essential The Sound of Broadway Music, a meticulously researched and informative book on musical theatre orchestration.