Here’s another reason Pat Routledge is a hero to us all.

Maria von Trapp interviews Maria von Trapp

The real Maria von Trapp sings with Julie on The Julie Andrews Hour, around the time of 1973 theatrical reissue of The Sound of Music.

%CODE1%

%CODE2%

Carol Channing on Sesame Street

Well, I had hoped to put up the infamous Leslie Uggams “June is Bustin’ Out All Over” interpretation in honor of the first day of this wondrous month. Alas, it has been pulled from the ranks on youtube, and virtually everywhere else on the internet.

So here’s something even more bizarre: Carol mackin’ it to a snake.

Nicholas Tamagna, Countertenor

Nick is an old friend of mine from high school whom all of us admired for his gifted ability with music. Whether it be instrumental or vocal, the range of his talent seemed to know no bounds and he went off to college to study music and then specifically, opera. I’ve been lucky enough to know Nick and to have worked with him on several occasions, academically and otherwise. We appeared together in high school in Funny Girl and Carousel (he was our Nick Arnstein & Billy Bigelow). I also worked on his incredibly amusing concept album – One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – the Musical; his final project for AP English. I would actually love to hear the latter, it’s been eight years since I last gave it a spin. He also was one of the most accessible and gracious people I’ve ever known, with a considerable sense of humor and the most unique infectious laugh I think I’ve ever heard in my life. All around, a really great friend.

Anyway, he’s just launched his updated website which introduces him for the first time as a countertenor. The countertenor is a male singer who can sing in the alto/mezzo-soprano range (some of the more flexible and rare venture up into soprano territory), either by use of a good falsetto or a ridiculous extension of the tenor range. He’s trained at UNCG, the Manhattan School of Music and most recently at Hunter College. A lot of years, kids, a lot of years. I wish him all the best.

Harvey Korman (1927-2008)

For fans of television, he’ll always be fondly remembered for the hilarious contributions he made on The Carol Burnett Show. For film fans, there was his tenure as a Mel Brooks favorite, most notably as Hedley Lamarr in Blazing Saddles.

Korman was a comic legend who left our world today at the age of 81. He had been suffering for several months as a result of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. His wide-ranging comic ability helped get him started on TV in bit parts, eventually landing on The Danny Kaye Show. He also was the voice of the Great Gazoo on The Flintstones (I never knew that!)

It was working with Carol Burnett that he would achieve his most lasting legacy. Her variety show ran from 1967-1978 and was among the most popular TV shows of the decade. Korman’s work as a comic foil was immense, most notably opposite the hilarious Tim Conway, who had the unstoppable ability to crack up the cast (but most especially Korman) in their scene work.

Here’s one of them:

And some bloopers:

Memorial Day at ‘South Pacific’

Frank Rich commented in an op-ed about the current revival of South Pacific and hits the nail on the head about the sort of impact this revival is having on audiences. Many of the feelings described are those I felt when watching this superlative production. I knew it was a hit, but I’m stunned at just how big a hit it is! Can you imagine? $1,000 in cash for a ticket? My word.

From the NY Times (in case you missed it):

Op-Ed Columnist

Memorial Day at ‘South Pacific’

By FRANK RICH

NEW YORK is a ghost town on Memorial Day weekend. But two distinct groups are hanging tight: sailors delighting in the timeless shore-leave rituals of Fleet Week, and theatergoers clutching nearly impossible-to-get tickets for “South Pacific.”

Some of those sailors served in a war that has now lasted longer than American involvement in World War II but is largely out of sight and mind as civilians panic about gas prices at home. “South Pacific” has its sailors too: this 1949 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical tells of those who served in what we now call “the good war.”

The Lincoln Center revival of this old chestnut is surely the most unexpected cultural sensation the city has experienced in a while. In 2008, when 80-plus percent of Americans believe their country is in a ditch, there wouldn’t seem to be a big market for a show whose heroine, the Navy nurse Nellie Forbush, is a self-described “cockeyed optimist” who sings of being “as corny as Kansas in August.”

Yet last week one man stood outside the theater with a stack of $100 bills offering $1,000 for a $120 ticket. Inside, audiences start to tear up as soon as they hear the overture, even before they meet the men and women stationed in the remote islands of the New Hebrides. Among those who’ve been enraptured by this “South Pacific” the most common refrain is, “I couldn’t stop myself — I was sobbing.”

This would include me, and I have been trying to figure out why ever since I first saw this production in March. It certainly wasn’t nostalgia. I was born two months before the show’s Broadway premiere in April 1949 and had never before seen “South Pacific” on stage. It was mainly a musty parental inheritance from my boomer childhood. My father had served in the Pacific theater for 26 months, and my mother replayed the hit show tunes incessantly on 78s as our new postwar family settled into the suburbs.

Like countless others, I did see Hollywood’s glossy 1958 film version. As the British World War II historian Max Hastings writes in “Retribution,” his unsparing new book about the war’s grisly endgame in the Pacific, “Many of us gained our first, wonderfully romantic notion of the war against Japan by watching the movie of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘South Pacific.’ ” But the movie of “South Pacific,” a candy-colored idyll dominated by wide-screen tourist vistas, is not the show. Its lush extravagance evokes the 1950s boom more than war.

In the 1960s, after the movie had come and gone, Vietnam pushed “South Pacific” into a cultural black hole. No one wanted to see a musical about war unless it was “Hair.” Unlike its Rodgers and Hammerstein siblings “Oklahoma!” and “The Sound of Music,” it never received a full Broadway revival.

Today everyone thinks they’ve seen the genuine “South Pacific” only because its songs reside in the collective American unconscious. “Some Enchanted Evening.” “Younger Than Springtime.” “There Is Nothin’ Like a Dame.” But few Americans born after V-J Day did see the real thing, which is one reason why audiences are ambushed by the revival. They expect corn, but in a year when war and race are at center stage in the national conversation, this relic turns out to have a great deal to say.

Though it contains a romance, “South Pacific” is not at all romantic about war. The troops are variously bored, randy, juvenile and conniving. They are not prone to jingoistic posturing. When American officers try to recruit Emile de Becque, a worldly French expatriate, in a dangerous reconnaissance operation, they tell him he must do so because “we’re against the Japs.” De Becque, who is the show’s hero, snaps at them: “I know what you’re against. What are you for?” No one bothers to answer his question. The men have been given a job to do, and they do it.

“South Pacific” isn’t pro-war or antiwar. But it makes you think about the costs. When, after months of often slovenly idling, the troops ship out for the action they’ve been craving, the azure tropical sky darkens to a gunpowder gray. Their likely mission is to storm the beach at Tarawa, where in November 1943 more than 1,000 Americans and 4,600 Japanese would die in less than 76 hours in one of the war’s deadliest battles.

This is a more fatalistic World War II than some we’ve seen lately. When America was sleepwalking on the eve of 9/11, the good war was repositioned as an uplifting brand. Nostalgia kicked in. Perhaps we wanted to glom onto an earlier America’s noble mission because we, unlike “the greatest generation,” had none of our own. The real “South Pacific” returns us to the war as its contemporaries saw it, when the wounds were too raw to be healed by sentiment.

That reflects the show’s provenance. It was hot off the press: a nearly instantaneous adaptation of “Tales of the South Pacific,” the 1947 novel in which the previously unknown James A. Michener set down his own wartime experiences in the Pacific.

Many theatergoers who saw “South Pacific” in 1949 had sons and brothers who had not returned home. Just 10 days after it opened at the Majestic Theater on 44th Street, The New York Times carried a small story datelined Honolulu. A ship had arrived there bearing “the bodies of 120 American war dead,” the remains of men missing in action since 1943. “Thus ended the last general search for the men who fell in the South Pacific war,” the article said.

Watching “South Pacific” now, we’re forced to contemplate Iraq, which we’re otherwise pretty skilled at avoiding. Most of us don’t have family over there. Most of us long ago decided the war was a mistake and tuned out. Most of us have stopped listening to the president who ginned it up. This month, in case you missed it, he told an interviewer that he had made the ultimate sacrifice of giving up golf for the war’s duration because “I don’t want some mom whose son may have recently died to see the commander in chief playing golf.”

“South Pacific” reminds us that those whose memory we honor tomorrow — including those who served in Vietnam — are always at the mercy of the leaders who send them into battle. It increases our admiration for the selflessness of Americans fighting in Iraq. They, unlike their counterparts in World War II, do their duty despite answering to a commander in chief who has been both reckless and narcissistic. You can’t watch “South Pacific” without meditating on their sacrifices for this blunderer, whose wife last year claimed that “no one suffers more” over Iraq than she and her husband do.

The show’s racial conflicts are also startlingly alive. Nellie Forbush, far from her hometown of Little Rock, recoils from de Becque when she learns that he fathered two children by a Polynesian woman. In the original script, Nellie denigrates de Becque’s late wife as “colored.” (Michener gave Nellie a more incendiary word in his book.) “Colored” was cut in rehearsals then but has been restored now, and it lands like a brick in the theater. It’s not only upsetting in itself. It’s upsetting because Nellie isn’t some cracker stereotype — she’s lovable (especially as embodied by the actress Kelli O’Hara). But how can we love a racist? And how can she not love Emile’s young mixed-race children?

Michener would work out this story in his own life. In 1949, he moved to Hawaii, where he would eventually make a third, long-lived marriage with a Japanese-American who had been held in an internment camp during the war. “South Pacific” works through this American dilemma for the audience, too. Years before Little Rock’s 1957 racial explosion, Nellie moves beyond her prejudices, propelled by life and love and the circumstances of war. She charts a path that much of America, North and South, would haltingly begin to follow. (In the script, we also hear of racism in Philadelphia’s Main Line.) “South Pacific” opened as President Truman was implementing the desegregation of America’s armed forces — against the backdrop of Ku Klux Klan beatings of black veterans.

Then and now, the show concludes with the most classic of American tableaus: Emile, Nellie and the two kids sitting down to a family meal. It’s hard for us to imagine how this coda must have struck audiences in 1949, when interracial marriage was still illegal in many states (as it would be in 16 until 1967). But nearly 60 years later, this multiracial family portrait has another context. The audiences watching “South Pacific” in this intense election year are being asked daily to take stock of just how far along we are on Nellie’s path and how much further we still have to go.

And so as we watch that family gather at the end of “South Pacific,” both their future and their country’s destiny yet to be written, we weep for the same reason we often do when we experience a catharsis at the theater. We grieve deeply for our losses and our failings, even as we feel an undertow of cockeyed optimism about the possibilities of healing and redemption that may yet lie ahead.

Sydney Pollack (1934-2008)

When you consider that the mere fact of his illness was a well-guarded secret, the death of Sydney Pollack is a rather unexpected loss to the film world. I have enjoyed Mr. Pollack’s work both on the screen and behind the camera, as he enjoyed a second career as a character actor long after he had been established as a noted director. I had most recently seen him offering stellar support to George Clooney in the excellent legal thriller Michael Clayton (which Pollack also co-produced).

Pollack began his career as an actor, studying with Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse in the mid-50s. He made one appearance on Broadway in the short-lived The Dark is Light Enough, a comedy that starred Katharine Cornell, Tyrone Power and Christopher Plummer. The play, written by Christopher Fry, lasted 69 performances at the ANTA Playhouse. Shortly afterward, he would move into television direction from which he would eventually launch his film career.

His most notable films include the searing indictment of ’20s dance marathons, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? with Jane Fonda, Michael Sarrazin and an Oscar-winning Gig Young, The Way We Were with Robert Redford (who was a life-long friend of the director) and Barbra Streisand, Absence of Malice with Paul Newman, the gender-bending comedy Tootsie with Dustin Hoffman (and Pollack’s uncredited turn as the agent who famously offers the classic line “No one will hire you.”) and would win the Oscars for Best Picture and Director for Out of Africa, a rather overrated period drama with Redford and Meryl Streep. Pollack was also nominated as director for Horses and Tootsie, as well as producing nominations for Tootsie and Michael Clayton.

Pollack would direct twelve actors to Oscar nominations: Jane Fonda, Gig Young (won), Susannah York, Barbra Streisand, Paul Newman, Melinda Dillon, Jessica Lange (won), Dustin Hoffmann, Teri Garr, Meryl Streep, Klaus Maria Brandauer and Holly Hunter. He also produced, executive produced or co-produced many films, including most of his later work. His post-Africa work never really maintained the stature of his early pieces. Aside from the blockbuster The Firm, he directed the unnecessary remake of Sabrina, Random Hearts, The Interpreter and Sketches of Frank Gehry. He also had served as host of “The Essentials” on Turner Classic Movies.

Cancer was the cause; he was diagnosed nine months ago. He is survived by his wife of 49 years, Claire, and two of their three children. He leaves behind a relatively small but important body of work in various areas of the film world.

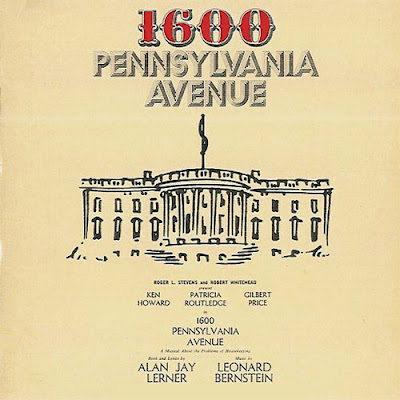

"A Musical About the Problems of Housekeeping"

"Enchanted"

I finally caught up with Disney’s Enchanted this afternoon. I had wanted to see it back in November, but considering I’ve been to the movies four times in 9 months, you can see that my priorities seem to have strayed from the silver screen. Anyway, thank goodness for these uber-quick DVD releases they do now. (Does anyone remember when they use to release VHS for rentals only for about six months before they sold them to the general public?)

The film was quite charming and highly amusing, stealthily irreverent with tongue in cheek. So much so, the old school ending seemed overly treacly as a result (the point at which the film loses steam is during the ballroom sequence, just prior to Susan Sarandon‘s homage to Maleficent). I enjoyed all the celebrations/send-ups of the Disney feature: Julie Andrews serving as the narrator, the old school animation (with includes the original Buena Vista logo used on the older Disney releases) to the more obscure, such as cameos from Paige O’Hara, Jodi Benson and Judy Kuhn (who’s quip was one of the funniest lines in the film), also having fun with fairy tale conventions (“Happy Working Song” anyone?) The score was cute and served the project well – I only hope no one gets the brilliant idea of putting this onstage in two years, we’ve had enough of that. (The songs, with the exception of that awful warbled mess that they tried to pass off as a waltz in the ballroom scene, were pleasant. I’m still glad the kids from Once won the Academy award).

However, the main reason I wanted to see the film was Amy Adams. I’ve been a huge fan of hers since I happened upon the film Junebug back in 2005. Hers was the most memorable by a supporting actress that year; and was pleasantly surprised when she was nominated for her breakthrough turn as the naive but warm-hearted expecting sister-in-law. If you haven’t seen the film, see it just for her – she is that remarkable. She also had a brief stint on The Office as an early love interest for Jim Halpert and was also Will Ferrell’s amour in Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby. I would venture a guess she has gained considerable clout with her star-turn as Giselle here, with an amiable singing voice and that wholehearted likability working in her favor. (She’s soon to be Sister James opposite Meryl Streep’s Aloysius in the upcoming film version of Doubt).

Certain things were pleasantly surprising: James Marsden as a musical theatre singer. I’ve only seen him in action movies (and I haven’t seen Hairspray), so to hear him bust out in song was impressive. Not to mention how hilarious he was as the brazenly fantastical Prince Charming, particularly in his encounters with New Yorkers (and technology, his scene with the “magic mirror” aka TV is priceless). Patrick Dempsey was affable as the love interest. Idina Menzel was a wet mop as his irritating girlfriend (thankfully not singing).

On top of that, it was a virtual who’s who of Broadway talent: Tonya Pinkins as the pending divorcee, the aforementioned Kuhn, O’Hara & Benson, Edmund Lyndeck (the original Judge Turpin in Sweeney Todd) as the decrepit homeless man, Joseph Siravo (yay Piazza!) as the bartender, Helen Stenborg, and Harvey Evans were the people I recognized. I’m sure there were more.

Like I said, the only problem I really had was the final 20 minutes or so. They’d had fun with the cleverness up to that point, but as they reverted to the formulaic, the sense of fun in the film waned an so did my interest. But overall, a pleasant little picture from Disney.