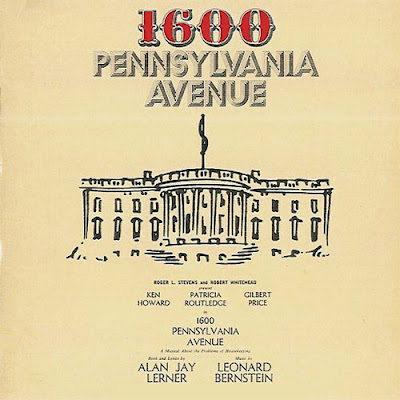

On February 23, 1976, the musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue had its world premiere performance at the Forrest Theatre in Philadelphia. The much-anticipated collaboration between musical theatre titans Leonard Bernstein and Alan Jay Lerner had been rehearsing in Manhattan for the previous weeks under the direction of Frank Corsaro and choreographer Donald McKayle. Tony Walton had designed the sets and costumes. Sid Ramin and Hershy Kay charted the orchestrations. Coca-Cola had put up the entire investment for what was looking to be Broadway’s big Bicentennial musical. This was the start of a pre-Broadway tour; and odyssey that would incidentally take the Presidential musical to the three cities which served as our nation’s capital.

Leonard Bernstein made a pre-show curtain speech in which he expressed his nerves and apologies to the Philadelphia audience for having canceled the scheduled first preview the night before. “The only trouble is that the scenery didn’t get here until Saturday afternoon, which is a mere three days ago and that meant that our most excellent company could not touch foot to stage until that moment.” He seems almost too apologetic, offering a flattering, “I know that you are the best trained out of town public in the whole country” and warns that “…this evening may be a long one; a long haul marred by pauses in which scenes simply do not appear uh and which you are subjected to the awful agony of sitting in black silence where nothing seems to be happening. If this should occur – which I perfectly hope it doesn’t – please know that we are all sharing your agony and that we are trying to make it as brief as possible.”

The musical starts with a mournful Prelude, whose melody is woven into the fabric of the entire score. This leitmotif will be somewhat jettisoned before the show reaches the Kennedy Center, as a new opening and a more traditional and livelier overture will be developed. As it played in Philadelphia, the show was considerably more somber. In a year of Bicentennial celebrations, a musical about the problems of housekeeping (as it was billed) made a fatal error in highlighting the less than commendable aspects of American history, a relentless critique where audiences had anticipated something more jubilant and celebratory.

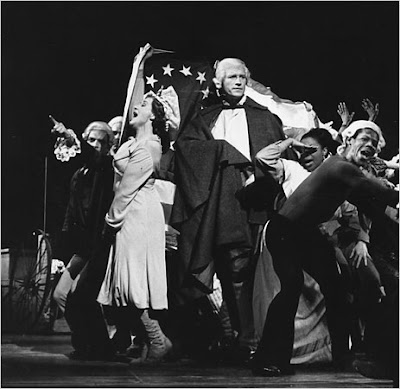

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue ultimately became a concept musical with footnotes. While presenting this tapestry of American history from 1800-1900, the revue-like musical was also a play-within-a-play. The “actors” stepped out of their characters to provide a contemporary perspective and analyze and debate race relations in American history. After establishing what the play is about (which briefly descends into minstrel show banter that comes out of nowhere and goes nowhere), the company prepares onstage for the first scene, finding places, making sure Washington’s teeth are around and assembling to sing “Ten Square Miles on the Potomac.” It’s a fantastic number, but not quite appropriate for establishing the tone of a musical.

Lerner had originally envisioned the show as a reaction to the corrupt Nixon administration and Watergate scandal. Our democracy would be seen metaphorically as a musical in perpetual rehearsal and in search of structure. One actor (Ken Howard) played all the Presidents, one actress (Patricia Routledge) all the First Ladies, while a black actor (Gilbert Price) and actress (Emily Yancy) portrayed four generations of a White House servant family.

Arthur Laurents was sought to direct. He told Bernstein and Lerner that they were writing a show about Black America and that it should be about the servants. Bernstein and Lerner disagreed and Laurents ultimately passed on the project. What the show needed more than a strong script was a strong musical theatre director with vision. Unfortunately, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue never received either. Lerner was also good friends with the CEO of Coca Cola, who was convinced to allow the company to be the sole backer ($900,000). A rush was put on to bring the yet unfinished musical to Broadway in time for the Bicentennial.

In the most arresting scene of the first act, and ultimately of the entire musical, the audience is introduced to Abigail Adams. Patricia Routledge dominates the scene, singing what would become the score’s most famous number “Take Care of This House.” It is Mrs. Adams who brings Lud, a runaway slave, into the White House to serve as “the servant bell,” a messenger between the First Lady and the serving staff. Routledge brings empathy and warmth (and great humor) that is otherwise lacking in the show. As both the actress and the First Ladies, she is both the show’s heart and the voice of reason.

Ken Howard revisits Thomas Jefferson, a role he played in the far more successful 1776, for the amusing “The President Jefferson Sunday Luncheon Party March” which only really tells the audience that the third President had an affinity for importing foreign cuisine, while not-so-subtly hinting at his affair with Sally Hemmings. An unlikely scene follows in which he admits to the young Lud (who is writing a letter to Mrs. Adams) his disappointment at the concessions made for allowing slavery in the founding of the country. It is at this point the set breaks down leaving three minutes of dead silence onstage.

The War of 1812 and the burning of the White House are depicted in a lengthy musical scene known as the “Sonatina.” Bernstein’s music was some of his most interesting and the song’s concept was quite brilliant. However, its relation to the musical as a whole feels rather tangential. Nine minutes without the President or First Lady, while British officers ruminate over an abandoned state dinner before they light it on fire. It’s an eight minute sequence whose centerpiece is a variation on “To Tunes of Anacreon” which later became the melody for the National Anthem. It’s of exceptional quality but it exemplifies what is wrong with the musical itself: a series of historical anecdotes, amusing non sequiturs and tangents that lack cohesiveness.

The Monroes have a late night argument about sending slaves back to Africa, culminating in the “Monroviad.” This segues into Lud and Seena’s argument “This Time,” in which she expresses concern over his safety in DC. This leads the actors playing Lud and the President to step out of character to debate race relations, with some tension. (The first time since the opening scene anyone has “stepped out”). Their unresolved argument culminates in the President becoming James Buchanan, who is eviscerated for his ineffectuality in preventing the Civil War. He sings “We Must Have a Ball,” in which Buchanan’s idea of assuaging battle is to bring them together in a civilized party. Lincoln is elected and the South secedes as the curtain falls for the end of act one, which on this premiere night has ran one hour and fifty minutes.

The second act opened with the company singing “They Should Have Stayed Another Week in Philadelphia,” a catchy musical comedy number that might have been more at home in a backstage musical. The lyrics spoke of script doctoring, finding focus, and “fixing what stinks” pertaining to the efforts of the Founding Fathers. Once the reviews came out this was one of the first songs to be cut, as its metaphors inadvertently hit too close to home.

The debate prior to the act one finale continues. The audience quickly learns that the Civil War and presidency of Abraham Lincoln occurred during intermission as the action picks up again with Andrew Johnson. The black chorus sings “Bright and Black,” the promise of a better future for Black America in a post-slavery society though also expressing dislike of Johnson’s administration. The most interesting scene in the second act is a confrontation between the President and Seena, in which they have an open, honest discussion about racial America (also one of the only scenes worth salvaging from the Broadway libretto).

Then we have “Duet for One (The First Lady of the Land),” one of my all-time favorite musical theatre numbers. Routledge absolutely nails it on its first public performance. The unlikely nine minute showstopper became one of the only moments in the entire show that worked in any town. Ms. Routledge delighted crowds switching back and forth between a belty Grant and a coloratura Lucy Hayes with a flip of the trick wig, trading barbs, all the while singing of one of the most fascinating Presidential elections in American history (Rutherford Hayes gets the Presidency in exchange for removing troops from the South effectively ending Reconstruction and starting the Jim Crow era). Philadelphia likes this number and there are even some cries of “Bravo!”if the reception isn’t quite as vociferous as the mid-show standing ovations received in Manhattan.

The next twenty minutes are devoted to Chester Alan Arthur, who became President when James Garfield was assassinated. Reid Shelton has a memorable cameo appearance as the brash, corrupt Senator Roscoe Conkling (responsible for Arthur’s political success) who snidely refers to Arthur as “Your Accidency” when it becomes apparent that the new President won’t play dirty politics. The President warily agrees to host a dinner party for the Robber Baron elite of America (Rockefeller, Vanderbilt). For the evening’s entertainment, a minstrel show is presented highlighting the corruption of these men and insulting them. The audience responds better to this segment than I would have expected (having heard from original cast members that there were walkouts and even cases of booing at some performances).

The “actor” playing Lud has reached his boiling point over the race relations and continues the argument with the “actor” playing the President. Lines between the character and actor become intentionally blurred. The musical settles into disillusionment in “American Dreaming” an angry duet that further explores the actors’ frustrations as both angrily decide not to continue, which puts the play into a state of chaos and the “actors” into pure despondency. It takes the First Lady to bring the “play” back on track as the President admits that ultimately he wants to be proud of his country in spite of all the areas in which is has failed. The stirring finale “To Make Us Proud,” a choral anthem in the tradition of Candide’s “Make Our Garden Grow,” offers a musical resolution to the tension established in that opening prelude. Ken Howard’s last line resonates in the middle of the song, “By God, it’s beautiful. Edith, I don’t whether the problems of this country can ever be solved. But I do know one thing: that the man who lives in that house makes you believe they can be and for sure they never will be.”

And curtain. The first night ran well over three hours. The reviews and word of mouth are not good. Variety deems the show “A Bicentennial Bore.” However, the show attracts sell-out business, breaking a box office record at the Forrest Theatre in its last week before leaving for Washington. However, the Coca Cola, utterly embarrassed by the reception, starts to disassociate itself from the show removing its name from the billing (also taking the free Coke out of the rehearsal room). This musical about the problems of housekeeping would soon find itself with housekeeping problems of its own, with the director, choreographer and set/costume designer all departing company. No two performances were the same until the show was frozen on Broadway, and by that point 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue was one of the highest profile failures for Lerner and especially Bernstein, who would never again compose for Broadway.