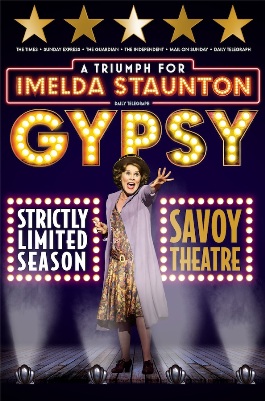

While it seems as if there’s a new Broadway revival of Gypsy every five minutes, London has not seen a production of the legendary musical since the original West End production closed in 1974. The musical, which tells the story of Rose Hovick and her two daughters, who would go on to become Gypsy Rose Lee and June Havoc, has been an instant classic since its 1959 Broadway premiere and contains one of the all-time great musical theatre leading roles. When I learned that Imelda Staunton would be headlining the first London revival in over 40 years, I decided to book my flight.

This new West End production is an import from the Chichester Theatre Festival, where Staunton and director Jonathan Kent previously collaborated on a successful Olivier-winning production of Sweeney Todd. The two also worked together on the UK premiere of David Lindsay-Abaire’s Good People. The critical response for Gypsy has eclipsed these two productions, garnering the sort of reviews that press agents can only dream about. Such notices can inflate my own expectations and lead to disappointment. Well, if anything, my expectations were exceeded. Imelda Staunton is giving a career-defining performance as Rose. Other Roses I’ve seen have given star turns (and were excellent), but Imelda just acts it. Her performance is epic in size, but unfailingly grounded. The cumulative result is one of the most searing star turns I’ve ever witnessed, and ranks among the top five performances I’ve ever seen in my theatergoing life.

The legendary cry “Sing out, Louise!” is heard from the back of the Savoy Theatre, and Staunton’s Rose, a diminutive spitfire, emerges from the shadows as though shot from a cannon. From these opening moments onward, there lurks a darkness in her, something a lot like rage, that sometimes rears its head at moments both expected and unexpected. These flashes sow the seeds for the inevitability of both “Everything’s Coming Up Roses” (harrowing) and “Rose’s Turn” (utterly devastating). But Imelda’s Rose is also charming, playful, resourceful, alert and unrelentingly maternal. Her singing voice is also up to the challenge, nuanced and warm on the ballads, but with the ability to fill the theater with a powerful, gritty belt when necessary.

In the lead-up to “Everything’s Coming Up Roses,” as favored daughter June elopes and the vaudeville act falls apart, Rose’s new plan to focus on Louise (out of spite, out of desperation) was met with some uncomfortable giggling by the audience, who seemed incredulous that this woman was even remotely serious. This nervous laughter turned to silent sheer terror within seconds as Rose beat June’s letter as though scolding a child, and again moments later as Rose grabbed Louise by the nape of her neck and forced her to bow on the line “Blow a kiss, take a bow…”

Her “Turn” was in another realm entirely. During the mock-strip portion, she alternated between mocking Dainty June and imitating Louise’s gestures from the “The Strip,” caustic, withering and crazed. In a performance filled with bold risks, Imelda’s greatest was a pregnant pause before the line “Momma’s gotta let go.” The audience sat compelled in pin-drop silence as Rose worked through her maelstrom of emotions. Every second was earned and never gratuitous, and it haunted me for hours afterward.

That Ms. Staunton is so tremendous is a wonder give than the production is using the detrimental revisions made for the 2008 Broadway revival. These changes made by librettist Arthur Laurents to accommodate Patti LuPone strip away both comedy and vulnerability, and make Rose more one-dimensional. (The brilliant Styne-Sondheim score remains untouched). It’s a testament to Staunton’s triumph that she manages to bring humor and considerable pathos in spite of these limiting alterations. For the record, a more traditional ending is restored and is staged in such a way that I was moved to tears.

Lara Pulver is a good Louise. If it’s a bit of stretch to see her playing a child, her performance becomes stronger as her character ages. She is at her best after she’s transitioned from awkward Louise to elegant Gypsy Rose Lee. I don’t think I’ve ever seen the final scene played better. Blessed with an exquisite voice, Pulver also adds some delicious flourishes to the end of “The Strip.” She has one especially thrilling moment: gawkish Louise clumsily drops her glove during the opening of “The Strip” and bends over to pick it up. A cat-call is heard from the balcony. She looks up and smiles. She’s suddenly aware of her own beauty and the impact of her own sexuality on an audience. Gypsy Rose Lee is born.

Peter Davison is a warm, ingratiating Herbie, tall and lovable, with a calming presence. There have been some complaints by West End critics about his singing, and I find it amusing that we live in a time where we expect Herbie to be a good singer. Dan Burton, who is the West End equivalent to Tony Yazbeck, is a sensational Tulsa, with eye-popping technique in all three departments and a superb American accent, to boot. The three strippers are a knockout comic trio, especially Louise Gold’s Amazonian Mazeppa, complete with deadpan Lady Baritone.

Kent’s staging doesn’t reinvent the wheel. It’s a traditional production in virtually every respect, but Gypsy is a tried-and-true classic and doesn’t need much tinkering. His great achievement here is in the work he has done with the actors, particularly in cultivating the central mother-daughter dynamics. Some of the original dances remain, while Stephen Mear has choreographed the rest in the spirit of Jerome Robbins (the most notable: a new, more elaborate “All I Need Is the Girl” for Burton). There is a somewhat reduced orchestration (no strings), which isn’t ideal, but doesn’t detract from the overall experience.

Imelda is worth the price of admission. I would go so far as to say she’s also worth the price of the air fare and accommodation. Beg, borrow or steal; whatever you have to do to get to the Savoy Theatre before November 28 (when this extended limited engagement is set to close). This is one for the history books and you do not want to miss it.

Also: there’s a new 2015 London Cast Recording. It sounds fantastic, and while it won’t supplant other recordings in the canon (namely the superlative original Broadway cast recording starring Ethel Merman), it offers a wonderful document for those of us who have seen the production.