I have a soft spot for depictions of romance between historical figures. There is usually a greater antagonizing force that heightens their intimacy significantly and also captures me on an intellectual level. These couples tend to not only share physical attraction, but they also respect and admire each other’s intelligence, wit, and talent. I doubt I would like 1776 as much were it not for the scenes between John and Abigail Adams, which anchor a great musical with humanity. Another show that comes to mind is the lovely British musical Robert and Elizabeth, which tells the story of how famed poets Elizabeth Moulton Barrett and Robert Browning came to be married.

Elizabeth Moulton-Barrett lived in seclusion in her sick room at her father’s London home with her eight siblings, her maid Wilson, and her dog Flush. The exact nature of what was wrong with her remains something of a mystery, but she had a life-long history of poor health, which has also been linked to the accidental drowning of her beloved older brother. She was prone to illness, weak, and often unable to sit up or stand.

Her father, Edward Moulton-Barrett was a manipulative tyrant who ruled his nine children with a puritanical fervor, forbidding any of them from getting married or even having contact with potential suitors with the threat of disinheritance. Elizabeth, the eldest and father’s favorite, was gaining notoriety as a poet. Poet-playwright Robert Browning, impressed by her writing, began a written correspondence with her.

Not wanting to disobey her father, Elizabeth tried to dissuade Browning from seeing her. However, Browning’s persistence paid off; he was granted permission to call and she was won over by his charm and sincerity. During their courtship, Elizabeth also showed improvement in her health. In direct defiance of her father, Robert and Elizabeth eloped and moved to Italy, where they remained happily married until Elizabeth’s death. Her father stayed true to his word and they remained permanently estranged.

Playwright Rudolph Besier turned their story into The Barretts of Wimpole Street, which opened in London in 1930 and became an instant hit. Katharine Cornell played Elizabeth in the original Broadway production, and the role became one of her signatures, with numerous tours, two Broadway revivals, and a 1956 telecast. MGM released a starry film version with Norma Shearer, Fredric March and Charles Laughton in 1934, and later a remake in 1957.

Robert and Elizabeth, as the musical adaptation would eventually be called, had an unusual gestation. American lawyer/songwriter (yes) Fred G. Moritt wrote an adaptation called The Third Kiss. Unable to drum up interest with Broadway producers, he sought other venues. A film company was interested, but only if the product was tested onstage first. British producer Martin Landau was brought in, and while I haven’t yet been able to ascertain how it happened, Landau opted to create a brand new musical entirely. Ronald Millar wrote the book and lyrics, while Ron Grainer (famous for the Dr. Who theme) wrote the music. Moritt was given the credit “from an original idea by.”

Millar’s book effectively adapts Besier’s play, and his lyrics are quite good if occasionally stilted (I tend to make allowances for specific period pieces). He includes many clever references to their poetry, most notably the haunting song “Escape Me Never,” which is built on Browning’s poem “Life in a Love.” But he also gives the many characters very distinct characterization in their songs. Grainer’s music is lush and soaring; unashamedly romantic, but never obvious or cheap. His gift for melody is enterprising and occasionally surprising, particularly in the more upbeat numbers for the secondary characters. The singing requirements are considerable: legit voices, arias, duets, trios, includes sextet, septet, octet (the jaunty “The Family Moulton Barrett”), and even a nonet (the wistful “The Girls That Boys Dream About”), as well as a couple of full company numbers.

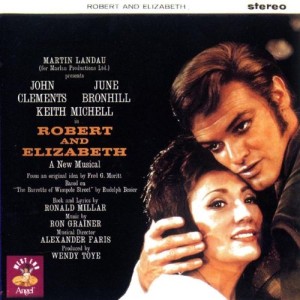

Keith Michell, who had achieved great success in the original London and Broadway companies of Irma La Douce played the dashing Browning. Coloratura soprano June Bronhill, who had great success in bel canto opera, the original Australian company of The Sound of Music, and famously The Merry Widow, was Elizabeth. John Clements played Edward Moulton-Barrett. The production opened on October 20, 1964 at the Lyric Theatre. While old-fashioned in its style and sensibility, Robert and Elizabeth clicked with audiences and proved a major success for Bronhill. An original London cast album was recorded by HMV. The show ran 948 performances, closing on February 4, 1967, though it failed to break even due to its high running costs.

There were plans to bring the show, with Bronhill and Michell reprising their roles, to New York, but litigation halted that. The most commonly mentioned reason is a rights issues with the estate of playwright Besier. However, there was also litigation by Moritt, who was interested in protecting his original un-produced property (which at this point, no one wanted). Moritt’s suit wasn’t settled until 1969. Instead, Bronhill took the show to her native Australia in 1966 for a seven month run opposite Denis Quilley. Ultimately, neither Robert and Elizabeth nor Bronhill ever came to Broadway.

Singing-wise, the role of Elizabeth has a higher placement than most musical theatre soprano roles, with lots of money notes above the staff. Her want song, “The World Outside,” finishes on a high A, and each consecutive solo goes higher and higher. The second act opens with Elizabeth’s “Soliloquy,” an operatic aria comprised of major motifs from the want song and the major love duet “I Know Now,” providing the dynamic shift in Elizabeth’s arc (as well as a breathtaking high C). Her eleven o’clock moment is a brief, but show-stopping defiance of her father called “Woman and Man,” which ends on a shock-tactic D above C (which some think is higher than it actually is because the note comes as a total surprise).

Bronhill sings the material with taste, elegance, and a warm intensity; her technique is impeccable and her diction is flawless (you can make out precisely what she’s singing on a fast arpeggiated chord to high B in “Woman and Man”); one of the greatest soprano performances in cast album history. I can find no evidence that Bronhill had a matinee alternate, meaning she sang the hell out of this role 8 times a week for over a year and a half.

Productions of the show have been few and far between. Steve Arlen starred in a Chicago production at the Forum Theatre in 1974. There was a production starring Sally Ann Howes and Jeremy Brett that played Guildford, UK and Toronto, Canada in 1976-77. This was rumored to be a pre-Broadway tour, but nothing more ever came of it. In fact, the closest the musical has come to Broadway was a 1982 production at the Paper Mill Playhouse, which received mixed reviews. In 1987, the musical was revived as part of the Chichester Festival, resulting in a second cast album. This second recording is more complete than the original, containing music that isn’t even in the vocal score or libretto, but the singing – especially Gaynor Miles’ Elizabeth – is lacking.

I would love to see Robert and Elizabeth on stage, but there are several factors that work against my wish fulfillment. The cast is immense: Robert, Elizabeth, her father, her eight siblings, a maid, a cousin, a secondary love interest, and a cocker spaniel, to boot. All totaled, the show requires a cast of at least 40. Plus, there are opulent Victorian set and costume requirements. Also, the musical was seen as old-fashioned in 1964; it would probably be seen as a relic by most of today’s theatergoers. In the meanwhile, I’ll continue to cherish the gorgeous original London cast recording.

Finally, here is “I Know Know” performed by Michell and Bronhill on his 1971 BBC special Presenting Keith Mitchell:

%CODE1%